How Do Children Learn to Read?

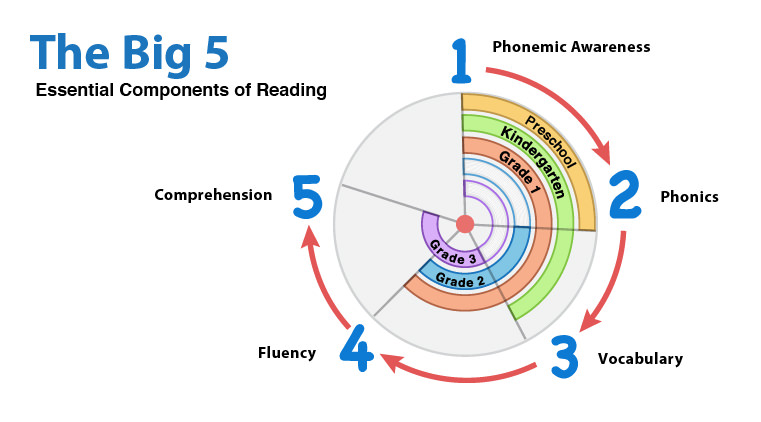

Learning to read involves five essential components, often referred to as the “Big 5”. These components are outlined in the National Reading Panel’s 2000 report Teaching Children to Read. In this report, the panel looked at over 100,000 published reading studies to determine the most effective evidence-based methods on how to best teach reading.

Children typically acquire these skills in succession, as development of each skill often leads into the next.

The above grade levels are an approximation of when you can expect your child to be working on each component.

1. Phonological and Phonemic Awareness

Phonemic awareness is one of the best predictors of future reading and spelling success. Research shows that children who enter kindergarten with strong phonemic awareness learn to read quicker than their peers without these skills.

Phonemic awareness is the understanding that words can be broken apart into individual sounds (phonemes). Phonemic awareness skills then, involve focusing on and manipulating phonemes in spoken language. It is important to note that phonemic awareness is an auditory skill; children do not need to know letter shapes and sounds (phonics) in order to develop basic phonemic awareness. As children develop an understanding of the sounds that letter symbols make, phonemic awareness and phonics skills are often practiced simultaneously.

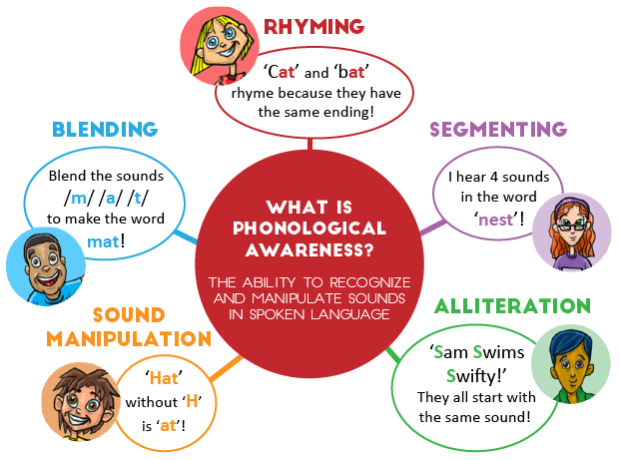

Phonemic awareness falls under the umbrella of phonological awareness, a broader term that refers to an awareness of all the parts of a word, not just the individual phonemes. Phonological awareness includes skills like rhyming and dividing words into syllables, while phonemic awareness includes skills like blending and segmenting the individual sounds in words.

There are many different tasks involved in developing phonological and phonemic awareness:

Rhyming

Rhyming words are words that have the same middle and end sounds. For example, bat rhymes with hat because they both end with the sounds /at/. Children typically learn how to recognize a rhyme before they learn to generate a rhyme.

To help a child learn how to recognize a rhyme, read rhyming books and play games that emphasize rhyme. For example, ask your child, “Which words sound the same at the end: sit, back, hit?” Use picture cards and have your child match pictures of objects that rhyme. Be sure to reinforce the rhyme by repeating the rhyming words. For example, “Dog rhymes with log because they both end in the sound /og/.”

Once a child is capable of identifying words that rhyme, practice generating a rhyme. For example, ask your child, “What’s a word that rhymes with map?” Play games that allow your child to think of a word that rhymes with a chosen word.

Rhyming helps children notice similarities and differences in words, an important component of auditory discrimination. More importantly, rhyming is a fun way to play with language, and a great way to promote early phonological awareness!

Practice your child’s rhyming skills with Captain Ray and the Rhyming Pirates! Click here to buy the book.

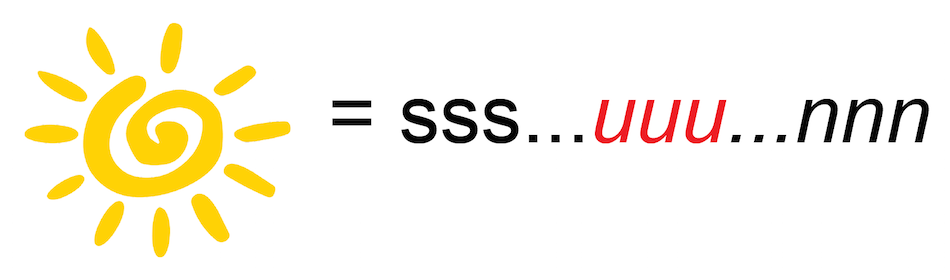

Blending

Blending involves listening to a sequence of separate word parts or phonemes, and combining them to form a word. For example, if you were to stretch the sounds in a word like sun, you might say sss…uuu…nnn, and then your child would blend the sounds together to say the word as a whole, sun. Practicing blending helps a child develop an understanding that words are made up of individual phonemes, a crucial component in learning how to decode, or “sound out” words when reading.

Blending is often practised as a progression of four stages:

- Compound words, pausing in between the two small words. (Say “base…ball” and child blends words into “baseball”.)

- Syllables (Say “lol…li…pop” and child blends syllables into “lollipop”.)

- Onset and rime (Say “j…ump” and child blends parts into “jump”.)

- Individual phonemes (Say “lll…aaa…sss…t” and child blends sounds into “last”.)

Practice blending skills with Slomo the Sloth! Click here to buy the book.

Alliteration

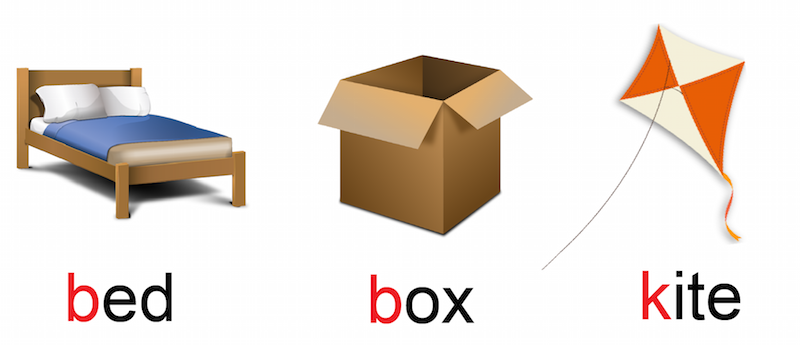

Alliteration is the repetition of the initial sound in a series of words. For example, the phrase marvelous monkey munch on muffins is an alliterative phrase because the four main words all begin with the sound /m/. Children must learn how to identify alliteration, as well as generate their own alliteration. Both identifying and generating alliteration involve isolating the initial phoneme in a word.

To practice identifying alliteration, read stories with alliterative phrases and make note of the repeated sounds. For example, ask your child, “Which words have the same beginning sound: bed, box, kite?”

To practice generating alliteration, ask your child, “What’s a word that begins with the same sound as fan?” Play games that allow your child to think of words that have the same initial sounds.

Have fun learning alliteration with Mischievous Mack in the Fantastic Floating Feast! Click here to buy the book.

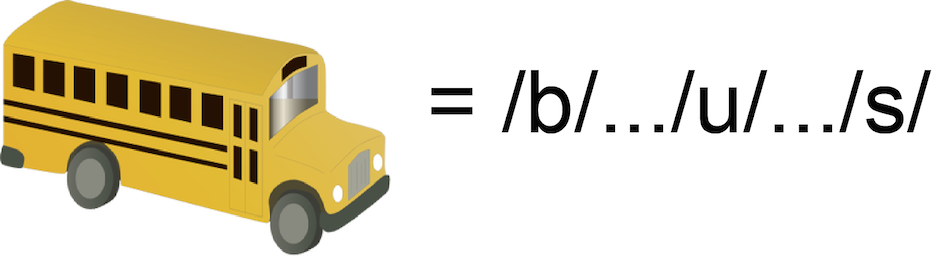

Segmenting

Segmenting is breaking words apart into smaller parts or individual phonemes. For example, say a word aloud, bus, and ask your child to say the word back to you one sound at a time: /b/…/u/…/s/. Think of segmenting as the opposite of blending. In blending, a child must combine individual sounds (or word parts) to form a complete word; in segmenting, a child must take a complete word and break it apart into individual sounds (or word parts).

Segmenting can also be practiced in a progression of four stages:

- Compound words (Say “sunset” and child segments word to say “sun…set”.)

- Syllables (Say “candy” and child segments syllables to say “can…dy”.)

- Onset and rime (Say “log” and child segments parts to say “/l/…/og/”.)

- Individual phonemes (Say “nest” and child segments sounds to say “/n/…/e/…/s/…/t/”.)

Practice your child’s segmenting skills with The Splitter Critter and the Greedy Pirates! Click here to buy the book.

Phoneme Manipulation

Manipulating sounds within words involves two main components: deleting a sound from a word, or substituting a sound in a word. To practice deleting a sound from a word, ask your child, “What’s fish without the /f/?” Your child would then answer, “ish”. To practice substituting a sound in a word, ask your child, “Change the first sound in rake to a /l/. What’s the new word?” Your child would then answer, “lake.”

Manipulating sounds within words is a difficult task for many children; it requires a solid understanding of how to isolate and segment the individual phonemes. Be sure that your child is strong in these areas before you move on to phoneme manipulation.

Practice manipulating sounds within words with Switch-a-Roo in The Great Riddle Race! Click here to buy the book.

2. Phonics

The National Reading Panel found that systematic phonics instruction made a significant impact on children’s reading success. The report also showed that phonics instruction is best done early (before Grade 1), helps prevent and remediate reading challenges in at-risk and struggling readers, and helps to improve reading comprehension and spelling in young readers.

Phonics is the understanding that letter symbols represent sounds, and that sounds can be blended together to make written words. It is also referred to as letter-sound correspondence, or sound-symbol correspondence, because children must understand that specific symbols (letters) match certain sounds (“This letter is a T, it makes the sound /t/”.) In order to decode, or “sound out” words when reading, children must acquire knowledge of the many different sounds that are represented by our alphabet.

Phonics should be taught in a fun, meaningful way, not as rote memorization or solely with worksheets. The best approach is to combine phonics with, and play active games involving real objects phonemic awareness that allow children to put their understanding of sound-symbol correspondence to use. Gather toys from the playroom, magnetic letters, foam letters, etc. and have fun identifying sounds and building words.

3. Vocabulary

Phonemic awareness and phonics can be thought of as the foundations of learning to read. They are the building blocks on which the other three components depend. However, the development of phonemic awareness and phonics are not sufficient in learning how to read for meaning, the ultimate goal of reading instruction.

This is where the other three components come in, beginning with vocabulary development. As children read, they come across new words that they may not have been exposed to in their oral language. In order for comprehension to occur, children must have word knowledge, or vocabulary, in addition to reasoning skills. Vocabulary is often taught as part of comprehension, as questions that ask a reader to determine the meaning of a word as it is used in the context of the story.

According to the National Reading Panel, vocabulary instruction is most effective when it is taught in a variety of ways. Children should be explicitly taught specific words selected from texts that they are reading. In addition to specific word instruction, children should be taught word-learning strategies, such as how to look up words in a dictionary, or how to determine a word’s meaning based on its roots. Finally, children can strengthen their vocabulary incidentally by participating in language-rich experiences both at home and at school, being read to, and reading independently.

4. Fluency

Fluency is the ability to read with speed, accuracy, and proper expression. It is an essential, but often neglected, component of reading. Readers who have not yet developed fluency produce slow, choppy reading. This will naturally impede a child’s comprehension, so fluency is often seen as the bridge to comprehension. If a child does not need to concentrate on decoding, he or she can focus on the meaning of a text much better.

Fluency develops gradually with a great deal of practice. The most effective approach to improving a child’s fluency is repeated oral reading practice. This might include reading the same story aloud multiple times, practicing lines from a play or reader’s theater, or guided reading instruction in a classroom. Additional independent reading practice (silent reading) is also beneficial, however, research has not yet determined this to have a clear impact on overall reading fluency.

5. Comprehension

Comprehension refers to a rich understanding of the meaning of the reading passage. It is the ultimate objective in teaching children to read. It is essential not only to academic learning (across all subjects), but also to life-long learning. Strong reading comprehension involves the following:

- Learning how to be aware of your understanding as you read and knowing how to deal with comprehension challenges as they arise

- Being able to answer the who, what, where, when and why questions about the plot, characters, and events of the text

- Generating your own questions as you read about what might happen next (predicting)

- Summarizing the main idea or message

- Making inferences about key ideas using clues from the passage

As a child is learning to read, be sure to foster each of these five areas specifically in a developmentally appropriate way. Have fun with sounds in words, practice phonics using real objects and letters you can hold, play word games and read material that emphasizes learning new vocabulary, read to and with your child daily, and ask questions as you read. Providing a language-rich environment will help to create a strong, independent reader who can successfully navigate each of the five components.

Get the Alpha-Mania books!

Buy Now!

References

Diamond, L., & Gutlohn, L. (2006). Teaching vocabulary.

Available: Link

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: an evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction.

Available: Link

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2001). Put reading first: The research building blocks for teaching children to read.

Available: Link

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2003). Early Reading Strategy: The Report of the Expert Panel on Early Reading in Ontario. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario.